Time to Decipher Narratives in Our History

@ERMedia91

This grand question has driven humanity to construct myths and historical narratives, shaping collective identities and territorial claims in on Earth and the Universe. Across centuries, nations and societies have devised stories to establish their place within a state or region. Over the past two centuries, the history of the Horn of Africa—particularly Eritrea and Ethiopia—has been deeply influenced by mythical claims, fueling conflicts and disputes among societies, nations and ethnic groups.What is the place of man in the Universe?

This article, presented in six parts, revisits major historical sources—though not exhaustively—to unpack the mythical narratives surrounding the region`s history. By analyzing the five paradigms—Aksumite, Orientalist, leftist, colonialist and international law—it aims to provide a nuanced understanding of how these myths were constructed, challenged, and ultimately contributed to the contested historical narratives of the region.

The complexity of reconstructing history

Reconstructing the history of ancient state formation in the Horn of Africa—particularly in presented-day Eritrea and northern Ethiopia—is neither an impossible nor an easy task. The challenges largely stem from the scarcity of literary sources and accessible oral tradition, which often provided only fragmented or insufficient information about the pre-colonial period. As one delves further into the past, these challenges grow increasingly pronounced.

While archaeological evidence offers some relief, it remains limited in its ability to fully reconstruct specific aspects of ancient states. Nevertheless, this study seeks to navigate these complexities and shed light on the region`s historical development, particularly in the wake of new historical interpretations emerging from Ethiopia.

The Contestation of History: Eritrea and Ethiopia

The history of Eritrea and Ethiopia has long been contested, particularly regarding the origins of statehood and civilization. Ethiopian scholarship has continuously sought to monopolize the narrative, asserting that civilization in the region belongs to Ethiopia.

According to many Ethiopian scholars, Ethiopia, in its modern form, lacks a significant number of credible historical events. On the contrary, much of the region`s ancient historical development is positioned within Eritrea`s domain. Eritrea, therefore, holds both territorial and historical significance in sustaining Ethiopia`s claims to statehood. Hence, this mythical construction of history relies on three flawed assumptions, (i) that Eritrea and Ethiopia were once governed under a singular state; (ii) that the region historically comprised [deleted] societies, (iii), that state formation in the region followed a linear historical trajectory spanning three millennia.

Countering Ethiopia`s mythical historical claims, championed by prominent scholars and supporters, has proven to be a formidable challenge. Deconstructing these narratives became an integral part of Eritrea`s armed struggle, though the challenge lay in avoiding the creation of another myth in place of the Ethiopian one. In response to this danger, Eritrean historiography sought to rely strictly on historical facts rather than myth-making. Owing to this principle, Scholars such as Jordan Gebremedhin (1989), Bairu Tafla (1995) have classified Eritrean historiography into distinct categories, including the Abyssinian tradition, Greater Ethiopia, and Marxist School. However, these classifications often overlap.

Rather than adhering to these conventional categories, this article introduces five broader paradigms—Aksumite, Orientalist, leftist, colonialist, and international law—to offer a regional perspective on how history has been Mythologized, challenged, and reinterpreted.

Aksumite Paradigm

The Aksumite paradigm portrays Eritrea as a frontier of the Aksumite Civilization. Within Ethiopian Scholarship, this perspective has gained prominence, treating Eritrea as a peripheral territory of the Aksumite state and often extending the region`s historical timeline to being with the Aksumite period. However, despite this marginalization, historical evidences suggest that Eritrea was an integral—if not central—part of the Aksumite civilization (Jordan 1989, Bairu 1996, Marcus 1994)

This narrative is constructed from two main sources; archaeological evidence and literal works. While archaeological discoveries are relatively recent, literary and oral sources date back to the pharaonic era of Egypt, as well as the Greek, Roman, and Arab trade networks.

Ethiopian scholarship, particularly narratives shaped by clergy and political elites, links Ethiopia`s statehood to the rise of the Aksumite civilization, framing it as the foundation of the region`s history (Teshale 1995).

However, this portrayal often marginalizes Eritrea`s role in Aksumite history. To fully understand Eritrea`s significance, it is essential to push the timeline of state formation further back to the Pre-Aksumite period.

Scholars such as Phillips (1997), Schmidt (2009), and Fattovich (2010) have identified evidence of state formation in the Pre-Aksumite period, which spans from the 2nd millennium BCE to the 1st century CE. Some historians extend this timeline to the 3rd millennium BCE, incorporating an intermediate Proto-Aksumite phase marking the transition to the Aksumite period. This extended chronology suggests, that Eritrea`s role in early state formation was far more significant than is traditionally acknowledged.

One major challenge in reconstructing ancient states in the region is the limited availability of sources. Archaeological evidence remains the most reliable method for historical reconstruction, as epigraphic and literary works are rare and often incomplete. For example, excavations in the Ona site in the vicinity of Asmara have revealed prosperous communities that thrived between 1000 and 800 BCE, engaging in agriculture, animal husbandry, and craft production (Phllipson 2010).

While archaeological evidence from Yeha, the capital of D`MT remains insufficient to provide full picture of its polity, available data suggest that D’MT was relatively advanced compared to settlements in Punt, Atbara, and Ona.

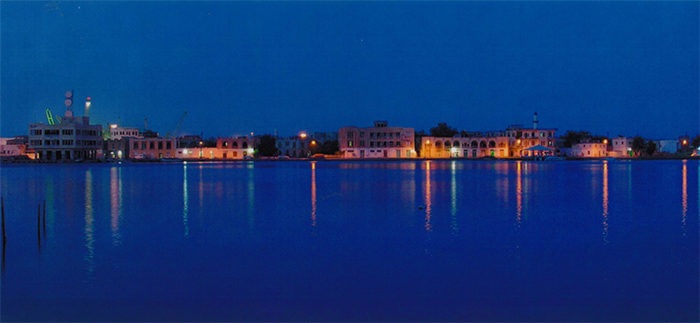

Similarly, the port of Adulis, which flourished in the pre-Aksumite period, played a crucial role in trade networks connecting the region with Egypt, Nubia, and Southern Arabia. The nature of Adulis before the rise of Aksumite dominance remains debated, but historical records suggest it was an established urban center by the early 1st millennium BCE.

Traditional interpretations attribute the rise of Aksumite civilization solely to Semitic communities, particularly those migrating from the Arabian Peninsula. However, recent archaeological discoveries dispute this assumption; highlighting the contributions of indigenous Hamitic and Nilotic communities to early state formation. Archaeological evidence from Ona, D`MT, and Adulis demonstrate that Aksumite civilization evolved from earlier local cultures rather than being solely influenced by migration from Arabia. While the Semitic presence played a transformative role, Aksumite civilization was not a direct import from Sabean culture but rather a fusion of indigenous and external influences.

Thus, the Aksumite civilization, which thrived from the 1st to the 10th centuries CE, was shaped by both internal and external forces. Politically, early Aksum was a feudal monarchy that consolidated polities across southern Eritrea and northern Ethiopia under a single rule. Over time, this state built a sophisticated administrative structure, diverse social systems, and a thriving economy.

It is essential to critically assess the Aksumite paradigm, which often positions Eritrea as a peripheral actor while ignoring its contributions to civilization. The conventional narrative suggests that history in the region beings with Aksumite dominance while overlooking earlier state formations that laid the foundation for its rise. While Aksumite civilization has often been framed as a purely Semitic tradition, it was, in reality, a product of gradual internal developments and external interactions. Most importantly, the territory that constitutes modern Eritrea remained central to these processes.

In conclusion, by examining the historical trajectory, this discourse challenges Ethiopia`s claims to exclusive ownership of these transformations. Instated, it argues that state formation in the region was the result of joint efforts between local societies and newly arrived communities across a broader territorial spectrum.