Go figure!

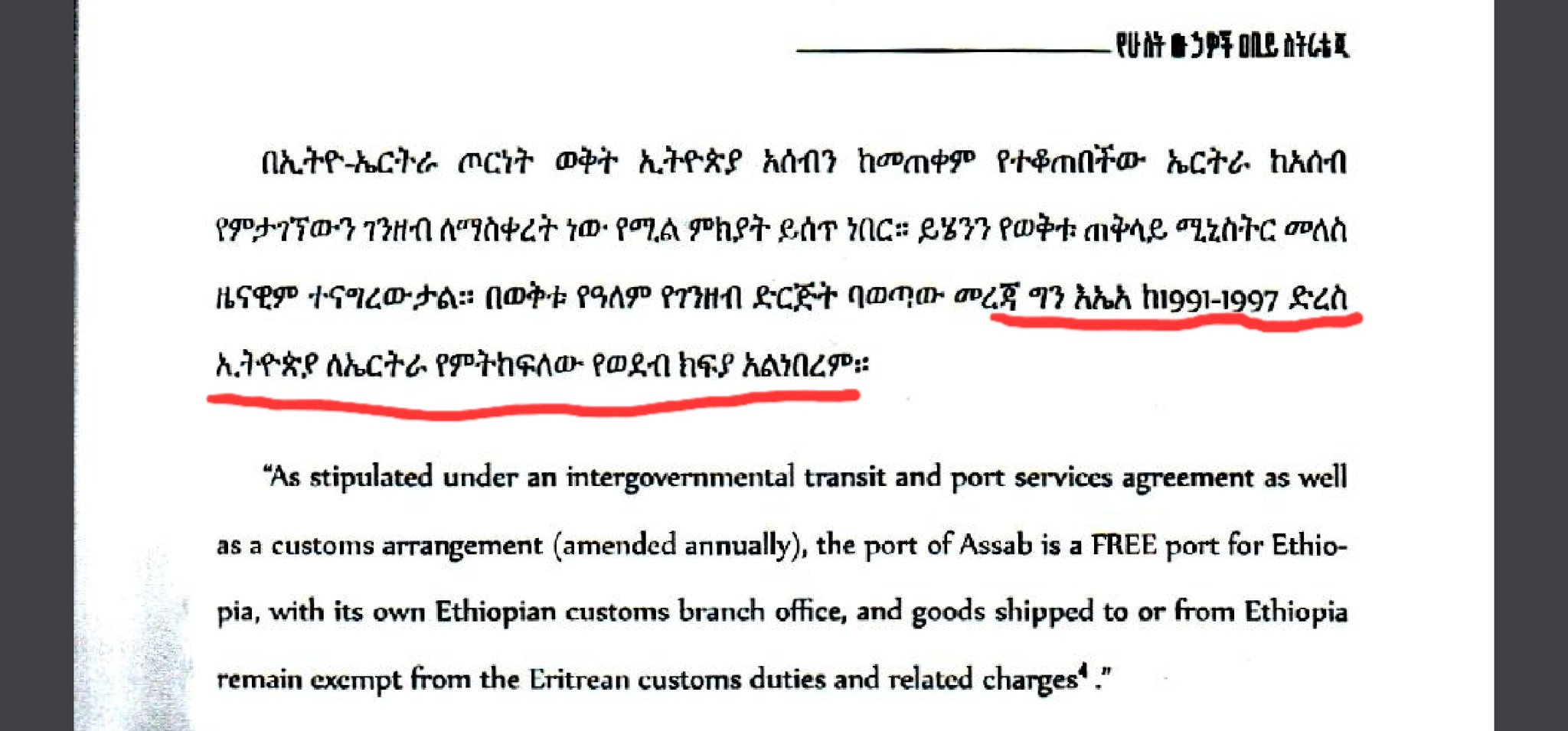

The utterly absurd document "strategy of two waters" shared by Ethiopia’s Institute of Foreign Affairs, says it all.

ዓለም ኣቀፍ የባህር ህግ ምንድን ነው? በግርማይ የማነ ከርያድ

መንግስቱ ሃይለማርያምኣልዒልኩም ብኽብሪ ቅበርዎ

ዝብል ትእዛዝ እዩ ሂብዎም።ይሄማ ምኑን ወንበዴ ሆነዉ!? ለኣላማዉ ሲል በጀግንነት የወደቀ ነው፣ ይልቅ ጀግንነትንና እራስን መስዋእት ማድረግ ከሱ ተማሩ፣ ኣሁን ሬሳዉን ኣንስታችሁ በወታደራዊ ኣጀብ በክብር ቅበሩት

ዝብል ዘይተጸበይዎ ትእዛዝ ኢዩ ሂብዎም።እዚ ደኣ እንታይ ወንበዴ ኮይኑ፣ ንዕላምኡ ብጅግንነት ዝወደቐ እዩ፣ ጅግንነትን ተወፋይነትን ካብኡ ተመሃሩ፣ ኣልዒልኩም ብወተሃደራዊ ዓጀብ ብኽብሪ ቅበርዎ

@EyassuYonasFrom the heart of a teenager to the soul of a true patriot, your journey has been one of selfless service, steadfast determination, and unshakable honesty. Few in this world, have given so much for their country—none with the passion and purpose you carry.

Dear Dr. Hussien:

Thank you for your thought-provoking reflections on the intertwined histories of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Your emphasis on the deep-rooted connections between the peoples of the Horn of Africa is both historically rich and culturally significant. However, certain interpretations and assumptions in your article warrant careful reconsideration, particularly in light of international law, contemporary geopolitics, and the evolving challenges of nation-building in the region.

First and foremost, it must be categorically stated that Ethiopia’s current landlocked status is not the result of any unlawful denial of access to the sea by Eritrea or any other party. Eritrea is a sovereign state recognized under international law, including by the African Union, the United Nations, and Ethiopia itself, following the 1993 referendum. The principle of territorial integrity, enshrined in the United Nations Charter (Article 2.4) and Article 4(b) of the Constitutive Act of the African Union, affirms the sanctity of colonial borders post-independence, regardless of their perceived historical justice. No regional grievance, however emotionally resonant, overrides these foundational legal norms.

Your critique, though well-articulated, appears to rely on a selective historiography that romanticizes imperial Ethiopian sovereignty over Eritrean territories while underplaying the colonial and postcolonial complexities that shaped Eritrean self-determination. The historical contributions of Eritreans to Ethiopian political life, as you rightly mention, highlight shared experiences, but these do not negate the right of peoples to self-determination, a right which Eritreans exercised with overwhelming support in the 1993 referendum.

What remains unaddressed in your analysis is the continued political crisis within Ethiopia itself, particularly the systemic fragility introduced by the 1995 Constitution, which institutionalized ethnic federalism. The very toxic constitution you allude to, crafted and upheld by the ruling party at the time, has entrenched ethnic division as a governing logic, exacerbating conflict and impeding national unity. Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s political approach, far from dismantling this ethno-political architecture, appears to oscillate between co-option and confrontation, depending on political expediency. This strategy not only undermines inclusive nation-building but also plays ethnic groups against one another, with devastating consequences for cohesion and peace.

Eritrea’s engagement with Ethiopia post-2018, particularly the rapprochement between President Isaias Afwerki and Prime Minister Abiy, was indeed welcomed with optimism. Eritrea embraced Abiy in the hope of genuine peace and regional cooperation. That trust was broken when Abiy chose to save the TPLF, a group long seen as a permanent time bomb between Eritrea and the Amhara. The TPLF, despite its record as a source of terror in the Horn, remains armed in violation of the Pretoria DDR terms. This decision speaks volumes. Even more troubling is Abiy’s ongoing war against the Amhara people, marked by mass atrocities and systematic repression, while the TPLF remains untouched and politically shielded. Despite the fact that both Eritrea and the Amhara resistance, particularly Fano, played a critical role in preventing Ethiopia’s disintegration during the TPLF’s northern offensive, Abiy has responded not with gratitude but with hostility, by criminalizing Fano, unleashing military campaigns against Amhara civilians, and now turning his belligerent posture toward Eritrea itself.

Eritrea’s sovereignty and independence must be acknowledged not only as historical outcomes but also as legal and political realities embedded in international norms. Conflating historical unity with contemporary political claims risks reviving narratives that have already been resolved through legitimate international processes. Rather than revisiting past contentions through unilateral assertions, the region would be better served by frameworks of mutual respect, non-interference, and forward-looking cooperation.

In conclusion, no one has denied Ethiopia access to the sea. What is at stake is how that access is pursued. If Ethiopia desires economic use of Eritrean ports, the appropriate path is diplomatic negotiation within the framework of sovereign equality, not historical revisionism. Ethiopia’s prosperity and stability depend not on relitigating the past, but on reimagining a future grounded in democratic governance, regional peace, and respect for the international rule of law.

The answer to your question can be summarised by one statement: the Tigray Republic agenda.