Q & A

Dexter Story: Bridging Academic Research and Living Tradition

By: Sabrina Solomon

https://shabait.com/2025/08/23/dexter-s ... tradition/

Aug 23, 2025

Q & A

Dexter Story: Bridging Academic Research and Living Tradition

By: Sabrina Solomon

https://shabait.com/2025/08/23/dexter-s ... tradition/

Aug 23, 2025

Dexter Story, a distinguished ethnomusicologist, composer, and producer, is celebrated for his profound academic and artistic connection to Eritrean culture. A graduate of UCLA with an M.A. in African Studies and a Ph.D. in ethnomusicology, his doctoral dissertation, Guayla Nation, explores the traditional Tigrigna music of Eritrea. A frequent visitor to the Eritrean National Festival since 2017, Story uniquely bridges his scholarly work with the living traditions he experiences firsthand.

Dexter Story, a distinguished ethnomusicologist, composer, and producer, is celebrated for his profound academic and artistic connection to Eritrean culture. A graduate of UCLA with an M.A. in African Studies and a Ph.D. in ethnomusicology, his doctoral dissertation, Guayla Nation, explores the traditional Tigrigna music of Eritrea. A frequent visitor to the Eritrean National Festival since 2017, Story uniquely bridges his scholarly work with the living traditions he experiences firsthand.

Known for his critically acclaimed albums Wondem and Bahir, Story’s musical work is heavily influenced by East African sounds, including Ethio-jazz. For him, African music embodies themes of joy, liberation, and resilience.

Your Ph.D. thesis, Guayla Nation, explores the cultural significance of guayla music. After years of academic study, how does experiencing this living tradition firsthand at the national festival, a microcosm of Eritrean culture, enrich or challenge your understanding?

I feel incredibly fortunate to experience the Eritrean National Festival firsthand. Guayla Nation was my attempt to shed light on a culture and a music form that is rarely studied in academic circles. What has been most enriching is seeing that guayla does not exist in isolation. It’s not just an isolated village or tribal music; it exists within the broader context of Eritrean nationalism, encompassing nine ethnic groups and six zones with regional differences. The challenge, then, is to allow guayla to maintain its own unique identity and story without overshadowing or undermining the unity and inclusivity that are so prominent here.

You’ve been a frequent visitor to the national festival, since 2019. What are your most significant observations regarding the evolution of Eritrean music and culture, and how have they influenced your own creative work?

I’ve been lucky to see the festival since 2019, with a couple of years missed. What I’ve observed is a revolution in expertise; this year, all the zones seemed to be at the same high level of performance. During my first visits, some zones were clearly more advanced than others. I have also seen more people engaging with the culture within the festival. I was previously limited in my understanding of Eritrean culture, but fortunately, coming to the festival has allowed me to incorporate new musical influences—even something as simple as a rhythm—into my own creative work. These observations inform both my music and my academic writing.

The national festival, is often seen as a reflection of Eritrea’s reality. As an academic specializing in this region, what are your insights into how the peaceful coexistence and unity among the country’s nine ethnic groups are nurtured and maintained?

The most striking thing about Eritrea is its inclusiveness. In a world full of racism, tribalism, and imperialism, the narrative here is one of mutual uplift. I’ve noticed a focus on community and family, rather than on the self. People are not preoccupied with, whether their ethnic group is better than others. It’s incredible to see how people speak about other ethnic groups, almost as well as they know their own. This sense of togetherness and community, is a truly remarkable and rare harmony.

There often appears to be a disconnect, between the peace and stability on the ground in Eritrea and the way the country is portrayed internationally. How do you reconcile these contrasting narratives?

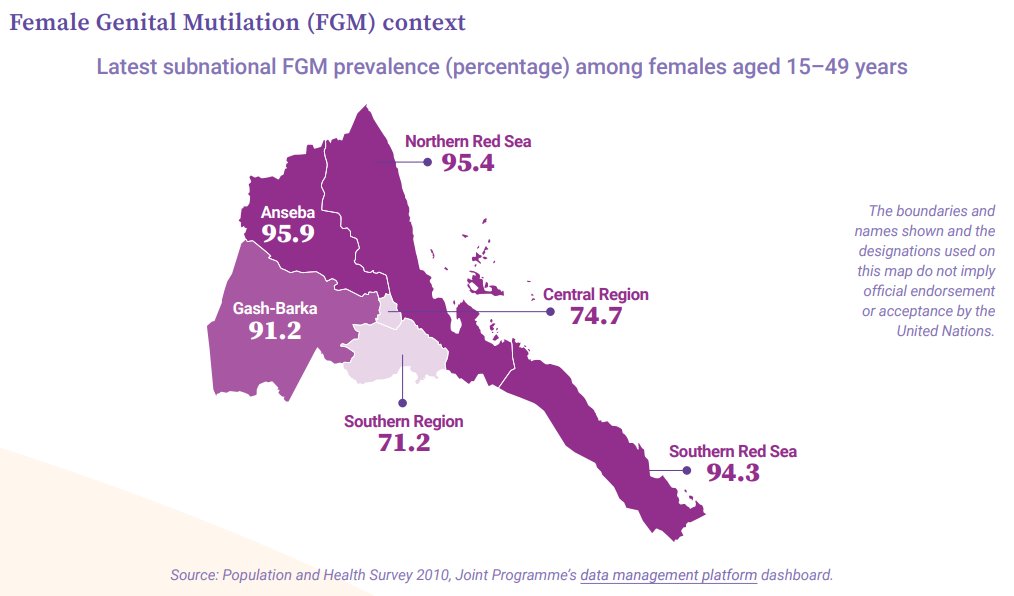

Reconciling these narratives, is perhaps the most challenging part of my work. The international conversation about Eritrea is often completely false. I have found this country to be one of the safest and most community-oriented places I have ever witnessed. It’s a country that also excels in gender parity. I’ve studied this extensively, but seeing it firsthand is another thing entirely. It’s fantastic to see that women have almost the same power as men, a stark contrast to many patriarchal societies. This equality is even reflected in my guayla research, where I’ve observed that the musical expression is as much a woman’s as it is a man’s. To anyone who questions this, I simply say: you have to see it for yourself. I’m not selling a narrative; I’m just telling you what I have personally witnessed on the ground. I hope more people come and see it for themselves.

Eritrean culture is often described as a form of “cultural resilience.” How do you see the festival reflecting this concept?

The festival itself is an interesting entity. Many people don’t know it was not allowed to be held in Eritrea for a long time and had to be organized in Bologna, first. The fact that it eventually came home and was established here is a testament to its cultural resilience. At the Expo, every ethnic group and culture is allowed full expression. It’s not just a facade; people bring their actual life experiences, their weddings, and their cultural artifacts to the space. You can see newlyweds in the Tigrigna space and newlyweds in the Kunama space. This ability of every ethnic group to fully express itself in one unified space is a powerful form of cultural resilience. I’ve never seen anything like it.

Beyond the official exhibits, what personal emotions have been most prominent for you while here?

The most enduring thing for me is the way people interact with each other. You see everyone talking, sitting down together, and having coffee—elders and youngsters in the same space. That is a quality of life that cannot be bought. It’s about working hard on your unity with people, which I think is one of the most profound things we can do as human beings. I’ve also never met an Eritrean who didn’t say “

hello” back to me. No one seems so upset that they can’t be polite. It’s a simple thing that has moved me to tears, and everyone has offered me tea or coffee. I love it.

As an artist who blends East African sounds with other influences, did any specific exhibition stand out to you?

The festival is incredible. I’d be underselling it to call it just a music and arts festival. It’s a showcase of the developments across all the zones, where each one represents its progress in areas like agriculture and industry, not just culture. This blew me away. What also impressed me was the sheer joy on the performers’ faces. As musicians, we sometimes get too serious about what we do, but here, the performers express a genuine inner joy. They aren’t just performing; they are being a part of something that speaks to them on a deeper level.

What message would you share with Eritreans in the diaspora? How can they best contribute to its development?

There is so much to learn from Eritrea. I applaud the unity I see in the diaspora, but there is a fantastic opportunity that comes from having a sovereign home, a place you can call your own. As a Black American, I don’t have that; I share my country with many other ethnic groups. Here, you can come home and share this land with your nine indigenous ethnic groups. It belongs to you. Come and invest your resources in this paradise. Trust me, being off the grid is a cleanse we all need. If I, as a Black American, am telling you to come and not lose this, you should.

Do you have a final message?

I am humbled by the privilege of being here to study guayla music. This research isn’t for me; my goal is to pass this knowledge on. I have spoken to my Eritrean colleagues about raising a new generation to appreciate and preserve the richness of this music. I hope to impart the knowledge I’ve gained to help younger Eritreans fully appreciate their incredible culture. This work would not be possible without the support of the Eritrean government, Ambassador

Zemede Tecle, Mr.

Yemane Ghebreab, and all my colleagues. I am truly grateful.